Sentence diagramming has tremendous value for students (and teachers!) of English grammar. Putting all of the words of a sentence on a diagram forces learners to identify the logical connections between different parts of the sentence. Students who diagram have to know how different parts speech work together to produce meaning; they can’t just memorize a few rules and label words without truly understanding their function.

But there’s an even more important benefit to diagramming: As the student moves on into high school, she can begin to use diagramming (as long as she’s studied it already) as a tool to fix weak sentences. Weak sentences usually stem from thinking problems—and diagramming can help the student locate those problem points.

A sentence which fits logically together is a sentence written in good style (poor style is most often the result of fuzzy thinking). Whenever a sentence doesn’t “sound right,”, the student should examine the logical relationships between the parts of the sentence. Diagramming the sentence lays the logic of the sentence bare and reveals any problems.

Consider the following balanced and beautiful sentence, from nineteenth-century poet Gerard Manley Hopkins:

Our prayer and God’s grace are like two buckets in a well; while the one ascends, the other descends.

Compare the sound of this sentence to a typical freshman composition thesis statement (this from an actual seminar paper I received several years ago from a student):

In Pride and Prejudice, her mother’s bad manners and wishing to get married made Elizabeth discontent.

While the second sentence makes sense, it’s an ugly sentence—the kind that makes parents and teachers despair.

If the middle-grade student is able to diagram both sentences, she’ll be able to see for herself why the first sentence resonates, while the second clunks.

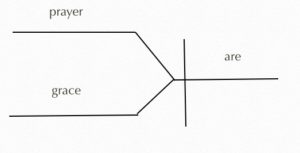

In the Hopkins sentence, the subject and verb of the first independent clause are diagrammed like this:

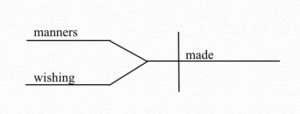

The second sentence also has a compound subject and single verb:

But although the second sentence is grammatically correct, it’s ugly because the two subjects are two different kinds of words. “Manners” is a noun, while “wishing” is a gerund—a verb form used as a noun. Words which occupy parallel places on a diagram should take the same form—as in the Hopkins sentence, where “prayer” and “grace” are both nouns.

If the student sets out to fix the style problem in the second sentence, she’ll also be forced to clarify her thinking. The noun “manners” represents something that Elizabeth’s mother is doing to her; it’s an outside circumstance. The verb form “wishing” is internal; it’s Elizabeth’s own action which is forcing her to be discontent. The two causes of her discontent aren’t parallel. So what is the relationship between them? Do the mother’s bad manners represent an entire social sphere from which Elizabeth longs to escape? Does she wish for a more genteel life, and does she wish to get married because that will allow her to move from one kind of life to another? Or is marriage itself Elizabeth’s driving passion? Does she simply resent her mother’s bad manners because they jeopardize her chances of attracting a bridegroom?

The middle-grade student won’t yet be thinking on this level, but learning to diagram sentences will allow her to begin to understand the relationship between style and thought—and prepare her for more complex high school writing.

For a slightly different illustration of this, consider the following sentence, also drawn from a freshman composition assignment, and containing a very common sort of beginning-writer error: “In addition to the city, Theodore Dreiser’s society is depicted in its people.”

This is the kind of sentence that almost makes sense; it’s clear that the writer has an idea in mind, but that idea isn’t coming through to the reader. But how can the student locate the problem?

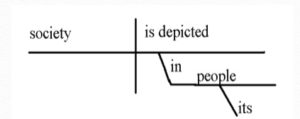

Through diagramming. In this case, the subject (society) and verb (is depicted) are diagrammed on a simple subject/verb line, with the prepositional phrase “in its people” diagrammed underneath the verb (it is acting as an adverb, because it answers the question “how”).

But where should “In addition to the city” go? It doesn’t seem to fit anywhere. Are the society and city both depicted? (If so, what’s the difference?) Is the society depicted in its people or in its city? (Neither is particularly clear.) The moral of this particular diagramming exercise: if you can’t put it on the diagram, it doesn’t belong in the sentence. The author of this sentence doesn’t exactly know what Dreiser is depicting, and he’s hoping to sneak his fuzzy comprehension past the reader.

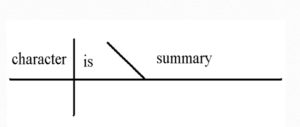

One final example, this one slightly more subtle: “Therefore, the character of Irene is a summary of women of the time.” This is a very common sort of beginner sentence: it makes sense, but it sounds immature. Why?

The tip-off to the problem is the slanting line, which indicates that the noun to the right is a predicate nominative. A predicate nominative must rename the subject. But “summary” is not another word for “character.” The two are not even roughly parallel; a character can’t be a summary any more than an elephant can be a mouse.

To sum up: Diagramming isn’t an arcane assignment designed to torture the student. It forces students to clarify their thinking, fix their sentences, and put grammar to use in the service of writing—which is, after all, what grammar is for.

Recommended Products

-

Sale!

Hansel & Gretel and Other Stories: Downloadable MP3

0 out of 5$12.95Original price was: $12.95.$9.71Current price is: $9.71. Add to cart -

Sale!

Dorothy and the Wizard in Oz: Downloadable MP3

0 out of 5$25.95Original price was: $25.95.$19.46Current price is: $19.46. Add to cart -

Fourth Grade Math with Confidence Instructor Guide

0 out of 5Starting at:$36.95Original price was: $36.95.$29.56Current price is: $29.56. Select options -

Sale!

Fourth Grade Math with Confidence Student Workbook A

5.00 out of 5$17.56 – $21.56 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

Sale!

Epic Heroes & Heroines of the Middle Ages

0 out of 5$11.21 – $14.96 Select options This product has multiple variants. The options may be chosen on the product page -

Sale!

The Well-Trained Mind: Essential Edition

0 out of 5$39.99Original price was: $39.99.$34.95Current price is: $34.95. Add to cart

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

Susan Wise Bauer

Join over 100,000 homeschooling families

For the latest offers, educational insights, products and more.

By joining you agree to our privacy policy.

11 thoughts on “Why Diagramming Matters”

Excellent article. Very well written and clear.

I enjoyed reading the article. It enhanced my curiosity to want to learn more.

I thought diagramming was fun, when I practiced in school. Now, I understand the why! The further I get from school, the worse my writing becomes, so thank you!

Thank you for a clear explanation of the benefits of diagramming.

I totally agree that diagramming does benefit one’s writing.

It overly complicates grammar. Students become more concerned about how to diagram than learning how to write sentences well. It may make sense to an adult but it’s often very confusing to a teenager. Poetry and novels can teach one how to write well far better than diagrams.

Hi CJ: I hope this helps clarify the matter a bit.

While sentence diagramming instruction can be done in the upper grades, it should be done, first and foremost, in grades K-6. As one who benefited from sentence diagramming in K-6 in the 1950s, I am convinced that it improves learning in three areas: sentence construction/punctuation, reading comprehension, and cognitive development.

By training the brain to read sentences as a combination of parts, rather than as one unit, sentence diagramming results in the following: (1) It becomes easier for a student to recognize the when and why of comma and semicolon placement; (2) Understanding complex sentences on standardized tests, which are mostly about comprehension, is easier; and (3) Since the extent of one’s cognitive skills is determined by the extent of one’s mastery of language, sentence diagramming in K-6 provides a critical foundation for cognitive development.

While reading is a key component, writing improves the most by writing and having a teacher review it for errors followed by re-writing the piece until correct. Since self-esteem is born of self-respect, it’s a student’s efforts leading to eventual success that enhances self-esteem by building self-respect.

About eight years ago, a local paper published comments written by five HS honor students about their future plans as new graduates. When I inquired about the poor quality of their writing, a person in the superintendent’s office told me she had actually cleaned up their writing.

That HS students who cannot write well are being given A’s in all their subjects tells us (1) the standards are too low, (2) the grading is too easy (grade inflation and expanding the A from 95-100 to 90-100 and the B from 90-94 to 80-89 makes grading much easier than it was prior to the 1970s), and (3) teachers still fear that correcting students’ writing hurts self-esteem and quashes creativity when it does neither.

That for the last 10-15 years college students have been demanding “trigger warnings” from professors and “safe spaces” from administrators is prima facie evidence that children are being coddled when parents and teachers should be helping them build the backbone needed to survive the demands and many, unexpected adversities one encounters throughout life.

The most effective way to learn grammar is by putting it into practical use by writing. There is little value in sentence diagramming. There are a multitude of studies that reflect that and it has been largely abandoned in schools.Homeschool curriculums appear to be the holdout and cling to practice of sentence diagramming.

Hi Lisa: Along with the explanation of the benefits of sentence diagramming instruction in my reply to CJ above, maybe the following will enhance clarification of the matter:

The fact that students’ standardized test scores have been lower for the last 50 years means that said test scores were once higher. Thus, the only logical first step to “finally” improving our K-12 education system is to review, evaluate and re-implement some or all the curricula and methodology in place when scores were higher.

That takes us back to the classrooms of the 1950s and ’60s when elementary schools had recess 2X a day, NO HOMEWORK, and students in grades 3-6 received sentence diagramming instruction.

While there are several reasons K-12 education has been so inadequate for so long, the primary reason is that the powers-that-be replaced the K-6 curriculum and methodology with reforms that failed miserably and still are.

The evidence of that is everywhere in the poor quality writing all over the Internet (Wikipedia has posted some of the worst of the worst) and in the gap-filled thinking of both those writers and the commentators on mainstream news — what I call “superficial thinking driven and controlled by emotion.”

That K-12 education and higher ed have been so inadequate for so many decades also means that many teachers under around age 65 were educated by the same failed system they’ve been expected to fix despite not knowing what they don’t know. This, in turn, means that any post-1980 (a guess-estimate) study requires careful scrutiny as there’s at least a 50% chance it isn’t as valid as claimed.

As parents and grandparents, we’ve been let down by all of America’s education experts, reformers, and professors.

In the first sample comparison, there is a second problem with the second sentence that isn’t mentioned but would be revealed were the entire sentence diagrammed.

The sentence is:

“In Pride and Prejudice, her mother’s bad manners and wishing to get married made Elizabeth discontent.”

Technically, by using the possessive “mother’s” followed by using “and” to connect “manners” with “desire” (substituted for the incorrect “wishing”), both the “bad manners” and the “desire to marry” belong to the mother, i.e. it’s her mother’s “desire to marry.”

Though a reader may logically recognize that it’s Elizabeth’s “desire to marry,” the sentence as written technically does NOT say that.

The simplest corrections are as follows:

“In Pride and Prejudice, her mother’s bad manners and her own desire to get married made Elizabeth discontent.”

“In Pride and Prejudice, a desire to get married and her mother’s bad manners made Elizabeth discontent.”

“In Pride and Prejudice, Elizabeth’s desire to marry and her mother’s bad manners made Elizabeth discontent.”

The last example uses this sentence: “Therefore, the character of Irene is a summary of women of the time.”

It might be easier for new writers to understand the reason it’s incorrect if the phrase “must restate” or “must accurately reference” is used instead of the more misleading “must rename.”

This is because a more accurate rewrite would use phrases like “is a reflection of” or “is illustrative of.” The words “reflection” and “illustrative” do not “rename” the subject “character,” but each does “restate” and “refer back” to it using a different word.

It wouldn’t be unreasonable for learners to associate the term “rename” with “synonym,” which is a totally different concept.